Hello again everyone!

After a two week absence from the LGG, we managed to have an extremely productive and interesting session of the group today. We discussed Ensslin’s Chapter 8, in which she wrote about poetry games, auteurship in video games, and the financial burden that creates a weight of commercial expectation around video games. Poetry games can influence the way we see and experience the written word. In fact, The Dream Machine had a particularly cool example of this. As the player gazes down into a strange abyss, when they speak into it the dialogue fades away into the bottom of the abyss, bouncing off walls. And when you get a reply, it starts small, and climbs to a crescendo. They do this all without sound.There’s a problem in the modern games industry that arises from the inevitable collision of art, vision, profit, and finance. There’s a tension between these two things; how successful can a game be without a big-name publisher? What even is the measure of a video game’s success? The fact that it can last twenty hours, stuffed to the gills with side quests that you’ll forget in a week’s time, or the fact that it is a tight, focused two-hour experience that haunts you for years to come? We talked about other tensions in games too – particularly in an open-world game with a cutscene driven story. Such large teams create games like Red Dead Redemption 2 and Death Stranding, that the design philosophies of the writing and the gameplay team don’t seem synchronized. This is where we get a disconnect, and not an enjoyable one at that.

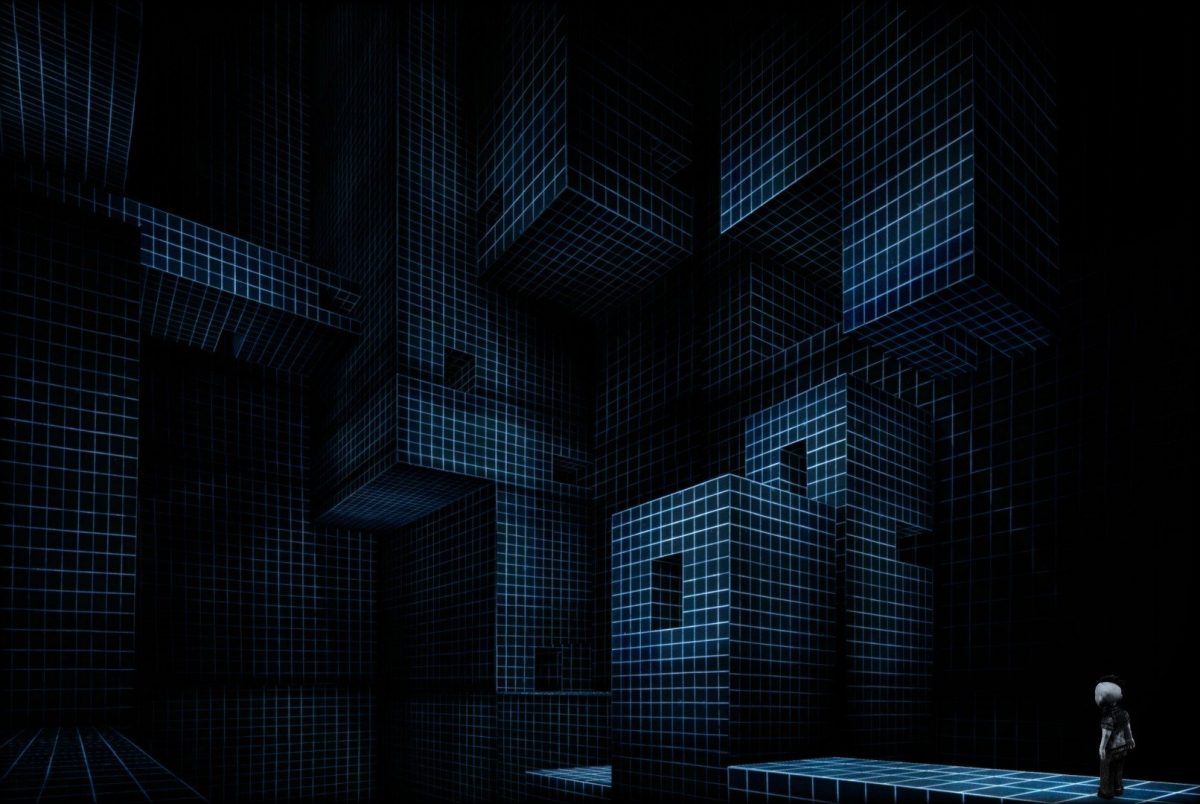

We continued with Chapter 5 of The Dream Machine, which is growing into its own at this point. The writing is stronger and more confident, and the puzzles are satisfyingly thought-out (once you find where to start). There are two separate dreams to solve in this chapter, and we’ve dabbled in both, but haven’t discovered the truth to either dream yet.

Next week we will finish up with Ensslin’s book, reading Chapter 9 and Chapter 10 (conclusion). Hope to see you there!